Is it time for the public to take back safety?

Features

The regulation complex

"While it may be true that morality cannot be legislated, behaviour can be regulated. It may be true that the law can’t change the heart, but it can restrain the heartless. It may be true that the law can’t make a man love me but it can restrain him from lynching me."

Martin Luther King.

With talk of regulations as overly complex and plagued by gaps and ambiguity, we talk to an MP and academics about the state of our regulations in the neoliberal era and ask: have the authorities, by changing regulations to fit the needs of the economy, sacrificed our needs for safety?

Faster production, keep costs low, be flexible: these are the mantras of our liberal economic order. How can these values fit with the care and deliberation needed to ensure that people are safe at home or work?

It’s a tension that is shaking the foundations of our regulations: a recent Sunday Times article, ‘the Scandal of Fire Safety’, (15 November 2020) pinpoints the blame for the Richmond House fire on the deregulation of rules that are meant to protect us. A commissioner of the London Fire Brigade noted “an emerging picture of increased risk across all types of buildings”.

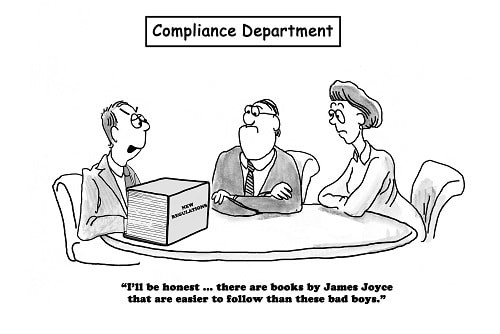

Are regulations protecting us or keeping us in a convenient state of confusion? Illustration: iStock

Are regulations protecting us or keeping us in a convenient state of confusion? Illustration: iStock

With Brexit negotiations over a dense legal treaty causing worries of more regulatory complexity, this article will examine ideas of regulation and whether in fact it is the complexity of rules that undermines their application.

It will examine why this is happening, whether something has changed in regulations themselves or whether our ‘ills’ are simply a result of cost-cutting? Is our ‘regulation complex’ preventing us from seeing what is really going on?

The danger of complexity: a tale of two fires

On why complexity matters, we should turn our minds back to the Lakanal House fire inquiry in 2013. At that inquiry into the deaths of six people in 2009, as reported by Elaine Knutt writing for Health and Safety At Work, “even the coroner and barrister struggled to follow the trail from Building Regs to Approved Document B to supporting guidance”.

Further, the jury heard conflicting evidence about the fire resistance of the panels, making any judgement about whether any one party followed any specific standard or regulation very hard to make.

Jump forward to Grenfell Tower: more deaths, recriminations, hand-wringing and inquiries. Commentators again made the point that regulations and fire safety were too disconnected and impenetrable. The chair of the Built Environment of Fire Sector Federation, speaking to Construction Manager, said there were gaps in accountability. “We’ve created gaps, not intentionally, but just by the nature of the complexity of the building process.”

Again, Approved Document B (ADB) came under examination. One fire expert refers to a bewildering array of “zig-zagging references, appendices, tables, guidance where ADB makes reference to 93 other documents”.

In their view, things used to be simpler. “In the past, the fire and rescue services inspected all properties and issued a fire certificate which stated what precautions a company had to take.”

So have we learnt the lessons of complexity? According to one developer who wished to remain anonymous, the new building regime for high-rises will involve complex judgements. “In practice, when it comes to an assessment of ‘System Hazards,’ which ask us to assess how risks inter-relate, there are complexities that require close attention and dialogue with the regulator. Yet the regulator is cash-strapped and mostly unavailable.”

What do we want from our regulations?

For Professor Andrew Watterson of Stirling University, a researcher and chartered health and safety professional, it’s three things. “I want specificity to ensure hazards are identified and action taken. Secondly, I want good evidence on hazards. Thirdly, I want a precautionary approach to be taken. If there are significant data gaps then the default position of non-approval of hazardous substances, equipment and processes kicks in.”

When it comes to avoiding another Grenfell Tower tragedy, Andy Slaughter, MP for Hammersmith and Fulham, agrees that first we need “clear and rigorous standards to ensure all materials and combinations of materials were inflammable. Secondly, a safe system of construction to ensure the materials were used in a way they were intended. And thirdly, independent qualified inspection to catch the rogues who cut corners, through incompetence or greed.”

Yet too often our regulations leave us with questions about the level of risk that people are expected to live with; and uncertainty about who does what and who is accountable when things go wrong?

Politics and regulation: a (very) short history of neoliberalism

Is politics to blame?

Foucault wrote that the German economic miracle of the 1950s was based on a new approach to the economy – a neoliberal approach – that ‘rescued’ the country. After the war, the German state was not only in a terrible material condition, any state planning had become illegitimate in the eyes of Germans and the international community.

The solution was massive deregulation, to let economic activity have the freedom from any constraints to build a new Germany. The example often given is the, at the time radical, removal of the State’s role in setting prices.

Perhaps it is not too fanciful to argue that after the collapse of the Keynesian approach to state-planned economics in the 1970s, the UK embarked on its own version and again sought legitimacy through economic liberalism.

It is a position that has since become hard-wired into UK politics until the present. Government should not only get out of the way of the market, it should be more market-like in its delivery of public goods, such as safety.

According to Paul Almond and Mike Esbester in their book, Health and Safety in Contemporary Britain, when it comes to how workplace safety is perceived, the “critical policy and media landscape gives grounds for seeing it reflected in the climate of neoliberal politics”.

For Andy Slaughter MP, the consequence “is a dangerous and unstable environment – domestically as well as industrially – by the combination of hollowing out public services and scything through regulation as if that were a benefit in itself regardless of the subject matter. We are now reaping what was sown.”

Cutting regulation or deregulation doesn’t always produce less complexity. It can produce more. On the removal of one ACoP, a safety professional complained of “having to locate the information in several different places, leading to more confusion and an increase in the number of documents people have to read”. More confusion, time wasted, things missed that go unchecked: this is how errors and, ultimately, where tragedy begins.

If bureaucracies are all about clarity and precision, what could be driving these deficient bureaucracies? Perhaps not only a politics that has embraced the myth of ‘market good, state bad’ but one that also sees ‘benefit’ in complexity?

Drivers of complexity

Societal change has a part to play. With the growth of a more diverse workforce and dispersed working (away from the traditional ‘heavy’ industries) and with more parties (and perhaps fewer collectives) to agree the formation of any rules that need to be made, all with different interests, there will of course be more complexity.

In the view of Paul Almond, Professor at Reading University with research interests in regulation and enforcement, regulations have “probably” become more complex in “posing requirements and prompting engagement with a broader range of issues, agendas, and ‘regulating’ bodies”.

Knowledge is also a factor. As knowledge increases about a certain health hazard and as knowledge increases about how to control it, so too does the inevitability of intervention by regulators.

For employers, general H&S duties are sufficiently broad to encompass any activity making a material contribution to a hazard.

Yet, it’s not only in relation to a particular hazard. Many aspects of social policy have health consequences: housing policy impacts on health; income inequality impacts on health.

This interconnection generates a huge increase in the number of actors and networks that need to be involved to address a particular, regulated, end.

A general expansion of law is another, though politics is at the heart of it. For Paul, “rules and regulations grow to subsume all these issues that we might otherwise seek to settle or resolve via politics, collective bargaining, or other means of negotiating and solving problems within society.

"This is done because regulation is meant to be apolitical, neutral, rational, and so regulating is offered up as a means of settling these issues outside of the political sphere – take them off the table as it were. This is a neoliberal ideological choice because it depoliticises things.”

There is an expansion of law to avoid social and political conflict. There might be an argument that in amongst all this confusion, laws are needed to step in to establish who was responsible for what. The more complex the regulation, the more law has to dig to get to the truth and justice.

Complexity in regulations has "a very useful and pronounced side-effect: it obscures the connections and channels through which actors and organisations might otherwise be held accountable."

Complexity in regulations has "a very useful and pronounced side-effect: it obscures the connections and channels through which actors and organisations might otherwise be held accountable."

Perhaps the most contentious driver might be self-interest on the part of duty-holders and the protection given to them by those in positions of authority.

Though Paul does not think that complexity in regulations is deliberate, he does think it has “a very useful and pronounced side-effect: it does obscure the connections and channels through which actors and organisations might otherwise be held accountable.”

As Paul says, accountability is often lost in a maze of temporary subsidiaries that hold liability but vanish on completion of the project. No one is to blame because the regulations that define ownership of the risk – and responsibility for redress when it goes wrong – allow people to hide.

Is complexity the real problem?

Others question that complexity is actually the problem. An ex-HSE inspector, speaking anonymously, told Safety Management “fundamentally, I would argue that the basic legislation for OSH is very simple. The challenge comes with technical details, which go out of date and are attacked for being ‘red tape.’ However, the fundamentals of OSH are simple.”

Andrew Watterson tends to agree with this. “With OSH I do not think most hazards and risks are too complex to deal with”. Instead, Andrew would lay the blame at cost-cutting. “Properly resourced and staffed OSH or Public Health departments can deal with a lot of complexity. You cannot separate off these two things.”

Andy Slaughter MP, is scathing about any idea that loss of life is inevitable: “There is a yawning gap between those who are making excuses for failure by saying it was all too complex or deregulated and the evidence now coming out of the Grenfell Inquiry. Cost-cutting and deception were knowingly used to approve products that could and did cost human lives.”

Though some complexity will be introduced when responsibility is passed down to duty-holders as a means of offering choice or freedom to ‘manage risks,’ “this complexity can be dealt with using the precautionary principle,” explains Andrew Watterson. “The problem of looking at things ‘case by case’ can be addressed by taking risks at the group level. We can avoid confusion, inertia, and delay.”

However, Andrew adds there is an ideological drive here. “The neoliberal agenda of cuts in budgets, cuts in staff, cuts in power, reduced inspections and enforcement, were all linked in one way or another to getting rid of ‘red tape’.” Much of this was disguised by claims of ‘better regulation.’ But cuts to regulation can drive complexity: “There will be greater clarity in regulations as opposed to no regulations.

"At Grenfell, if there had not been deregulation by stealth, then there would have been more checks and tests on building materials etc.”

Paul is also mindful of how the context regulations are created in can drive complexity. “It is also clear that the world and the risks within it have become more complex and demanding, and that the nature of the rules we have to govern us are also often unhelpful – emerging in a piecemeal way to plug gaps, often driven by crisis or events like Grenfell, producing a set of overlapping rules and differentiated requirements, introduced and handled across a fragmented state infrastructure.”

At Grenfell, if there had not been deregulation by stealth, then there would have been more checks and tests on building materials

At Grenfell, if there had not been deregulation by stealth, then there would have been more checks and tests on building materials

Instrumentalising complexity: the decentred state

In an influential paper from 2001, Julia Black’s Decentred regulation captures how we moved into a new post-regulatory world that reflects such modern political and economic developments.

Not state regulation, not self-regulation, both are defined as legal rules backed up by criminal sanctions, the so-called Command and Control (CAC) approach.

Instead, for Black “regulation is occurring within and between other social actors, for example large organisations, collective associations, technical committees, professions; without government involvement”. Decentred regulation leads to fragmentation and difference.

The reason we are on this path? Old-style government regulation is dismissed as inevitably stymied by a lack of knowledge of what it seeks to regulate: government cannot know as much about industry as industry does about itself.

In Black’s words: “Regulatory failure is based on the dynamics, complexity, and diversity of economic and social life, and in the inherent ungovernability of social actors, systems, and networks.”

Paul adds to this analysis: “I think that the aversion to top-down regulatory intervention and rule-setting has led to the growth of a much more pluralised and complex system of regulations, because it is meant to stem from the regulated population itself.

Yet, crucially, for Black, “decentring is, I believe, being felt in how regulations are becoming highly complex and dangerously inadequate.” This is even leading to a situation where “regulation is uncoupled from the activities of government.”

If government lacks the ‘knowledge’ to effectively regulate industry, the requisite knowledge must stem from many actors, where none dominate.

It is a kind of Tower of Babel model for how the state and regulation should work. Black: “Interaction between these social actors, and between them and the state, is complex. Regulation becomes two way, three-way or four-way process. Regulation is co-produced.”

Post-pandemic: re-centring regulation?

‘Inherent ungovernability’ does not sound like a manifesto for a safe future. If markets have the ‘invisible hand,’ societies need rules that at least appear to be just. Otherwise we have rule by wealth, a plutocracy. In their best form, regulations leave no doubt about who or what is responsible in the event of a catastrophe. Redress is possible but at the moment this doesn’t seem to be where we are.

The question arises whether the pandemic will trigger a change? To some degree what has gone wrong is simply the state’s ability to govern well, seemingly undermined by our current approach to regulations.

The Public Accounts Committee observed in 2018 that “the Better Regulation Executive established a complex bureaucracy across Whitehall” and this is picked up by Larry Eliot of the Guardian who wrote: “What Covid-19 has shown is that the state’s core functions of planning and delivering public services has been hollowed out.”

Yet, Professor Andrew Watterson has his doubts that any move towards regulations that are clear, specific and properly resourced is coming soon. “Yes, with the pandemic there has been confusion and yes, the failures have roots in the ‘better regulation’ ideology. But I am sceptical about a political change in attitude.”

Andy Slaughter MP, is in a unique position to influence change, but he knows it will be an uphill struggle. Addressing what has gone wrong about how we regulate safety and housing more generally will, he says, “require a comprehensive response led from the top of government, instead there is a piece-meal approach and confusion.

From the many types of unsafe materials that will need removal, to the effect on the housing market – and thousands of individuals and families – of whole estates becoming unsaleable, this is a generational crisis for the property industry.”

“I believe,” Andy adds, “the concerns around fire safety are indicative of a wider malaise over building standards and construction. The ‘planning revolution’ the government has announced, far from learning from the experience of Grenfell Tower, destroys 70 years of balance in the planning system by putting all the cards in the developers’ hands. We are in danger of building – or converting – the slums of the near future, not just unsafe but unfit for habitation.”

Which is another way of saying that regulations emerge from political choices and will be fought for in future struggles.

If we want a reason why this is important, we should listen to what Karim Mussilhy, whose uncle Hesham Rahman, lived on the 23rd floor of Grenfell Tower, has to say: “Until those in power make changes to the system, only God knows how many homes are safe. So listen and learn from those mistakes.

"We are here because the system failed to protect my uncle.” and 71 other souls.”

Matthew Holder held the post of Safety Management's interim Editor in 2020. He was previously Head of Campaigns and Engagement at the British Safety Council

FEATURES

How to build circular economy business models

By Chloe Miller, CC Consulting on 07 April 2025

Widespread adoption of a circular economy model by business would ensure greater environmental and economic value is extracted and retained from raw materials and products, while simultaneously reducing carbon emissions, protecting the environment and boosting business efficiency and reputation.

What does the first year on an accelerated net zero path have in store for UK businesses?

By Team Energy on 07 April 2025

The UK is halfway to net zero by 2050 and on a new, sped-up net zero pathway. In light of this, Graham Paul, sales, marketing & client services director at TEAM Energy, speaks to TEAM Energy’s efficiency and carbon reduction experts about the future of energy efficiency and net zero in the UK.

Aligning organisational culture with sustainability: a win, win for the environment and business

By Dr Keith Whitehead, British Safety Council on 04 April 2025

The culture of an organisation is crucial in determining how successfully it implements, integrates and achieves its sustainability and environmental goals and practices. However, there are a number of simple ways of ensuring a positive organisational culture where everyone is fully committed to achieving excellent sustainability performance.