A manager’s ability to recognise, understand and manage the emotions, concerns and attitudes of team members is critical for fostering a healthy and productive workplace, but luckily, the required ‘emotional intelligence’ can be learned through practical, hands-on training.

Features

Navigating the tightrope: the critical role of managers in workplace wellbeing and psychological safety

We all know the old saying, “people don’t quit bad jobs, they quit bad managers”. Well, it seems that it is true. A study has found that 57 per cent of employees have left a job because of their manager and an additional 32 per cent have seriously considered leaving because of their manager.¹ Managers are one of the top reasons people choose to stay or leave. Even if an organisation is thought of as having a supportive corporate culture, good benefits and employee wellbeing programmes, a poor individual manager can still be the root cause of an employee choosing to leave.

Photograph: iStock/SDI Productions

Photograph: iStock/SDI Productions

Almost 70 per cent of people say their manager has more impact on their mental health than their doctor, and that figure is equal to the impact of their partner.² Given that we spend a third of our adult lives at work it makes sense that managers contribute so significantly to how we feel.

In the intricate tapestry of organisational structure, managers act as the crucial thread that weaves together the strategic vision of the senior leaders with the operational fabric of the workforce. Their position, however, is one of precarious balance, teetering between the demands from above and the needs from below, a balance that is critical not only for achieving corporate goals but also for ensuring the health, safety and wellbeing of employees.

The management conundrum

Managers find themselves in a unique position, shouldering immense pressures that stem from a wide array of sources. They are expected to translate high-level strategies into actionable plans, manage teams with diverse needs and ensure that their departments meet their performance targets. This multifaceted role, coupled with the expectation to be both a leader and a confidant, subjects them to a level of stress that is both unique and intense. The impact of this stress is not confined to the managers alone; it cascades down to their teams, affecting overall job satisfaction and productivity.

The additional responsibility of protecting employees’ psychological safety, defined as the belief that one will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes, has increased since the pandemic. The Office for National Statistics reveals that depression rates have doubled since the Covid-19 pandemic began, forewarning of a growing mental health crisis, and yet the skills and confidence of managers to deal with this have yet to catch up in many instances.

Catching up is essential however, given that the correlation between psychological safety and physical safety in operational roles is increasingly recognised as critical for overall workplace safety.

Workers who feel psychologically safe are less likely to be injured at work, since they feel comfortable speaking up about safety issues without fear of retaliation and thereby foster drastically safer workplaces. A survey found that workers who felt psychologically unsafe were 80 per cent more likely to have been injured at work, requiring medical attention and/or time away from work. And conversely, workers who feel their employer discourages reporting potential hazards and safety issues were 2.4 times more likely to have experienced a work injury.³

This underscores the importance of fostering a workplace environment where employees feel supported and respected, which in turn can lead to safer physical work conditions.

Organisations need to move beyond outdated management methods where intimidation or bullying are permissible. Creating a culture of psychological safety involves providing a supportive environment where employees feel included, safe to learn, contribute and challenge the status quo without fear of retribution. And on the upside, this not only enhances physical safety, but also contributes to the overall health, productivity and sustainability of the organisation.

But how comfortable do managers feel about this responsibility, or perhaps more to the point, how many are truly aware of this responsibility? Many managers still pass issues of mental health and wellbeing to HR or occupational health departments, believing it to be their responsibility and not their own. But uncomfortable or unaware, without fully embracing this responsibility they will become a major roadblock to fostering wellbeing. What is required is that companies clearly establish managers’ wellbeing responsibilities and equip them to own that role.

Emotional intelligence: the keystone of effective management

Emotional intelligence (EI) – the ability to recognise, understand and manage one’s own emotions and those of others – emerges as a critical skill in a manager’s responsibility to protect psychological safety and promote employee wellbeing. Managers adept at recognising and managing not just their own emotions but also those of their team members can significantly enhance job satisfaction and productivity. EI enables managers to foster a supportive team environment, handle conflicts with empathy, inspire their teams and support those who are experiencing mental health challenges or poor wellbeing – all of which are indispensable for maintaining a healthy workplace.

This human-centric approach to management for many however is an unusual feature in the workplace. But the good news is that it can be taught.

The initial step to enhancing the EI of managers isn’t to simply teach them the theoretical aspects of EI. Traditional teaching methods, where information is primarily delivered in a lecture format, often lead to a situation where the majority of the learned material is quickly forgotten. The emotional impact of learning experiences, however, tends to have a more lasting effect.

The critical shortfall in many training programmes is that they focus on imparting knowledge without providing opportunities for practical application. As a result, not only is the time and financial investment in such training potentially wasted, but there’s also little to no change in behaviour or skillset among the participants.

The importance of experiential learning can’t be overstated. Just as you learned to speak by talking, to walk by getting on your feet, and to drive by getting behind the wheel, the development of EI skills requires practical, hands-on experience. For instance, understanding the mechanics of a bicycle doesn’t prepare you to ride it; getting on the bike and physically practicing does. Similarly, for managers to truly develop and improve their EI, they need opportunities to apply these skills in real-world situations, reflecting on these experiences and learning from them. A hands-on approach not only makes the learning process more engaging and memorable but also facilitates the genuine development of EI competencies that can be applied in their managerial roles.

Experiential learning: a pathway to improvement

Using an experiential learning model, such as that developed by Kolb, is a powerful and effective tool in upskilling managers, where they are immersed in a practical, hands-on experience that challenges them to solve real-world problems and make critical decisions.⁴ Working with our clients, Ripple&Co has seen a dramatic increase in the confidence of managers to take a human-centric approach and hold supportive conversations with employees when using this experiential model. It is the concept at the heart of Talkworks.

The training solution requires the involvement of specially trained facilitator-actors who enable participants to have authentic conversations while building their confidence and skills to support colleagues. Not only is it an experiential solution, but the managers are also immersed in simulated scenarios that are developed based on their company’s employees and workplace, thereby further engaging them in real-life situations. It provides a rare opportunity to learn and safely try out new behaviours, skills and conversations. You can watch an example of the training here.

Following Kolb’s model, participants first observe a roleplay between two actors and offer their reflections and suggestions for improvement, before breaking into smaller groups to try out the conversation for themselves in a safe environment supported by a facilitator-actor.

Eileen Donnelly is chief executive and founder of Ripple&Co. Photograph: Ripple&Co

Eileen Donnelly is chief executive and founder of Ripple&Co. Photograph: Ripple&Co

When delegates were asked – “To what extent does the following statement reflect how you feel? I feel confident about having a support conversation with a member of my team,” 87.5 per cent of delegates responded, “True of me or Very true of me,” and 100 per cent of delegates responded, “Somewhat true, True of me or Very true of me”.

The conversation is the crucial element in the manager’s toolkit. Other key elements of a human-centric approach are entirely based on a manager’s ability to be able to communicate skilfully with empathy and authenticity.

Consider the following key elements that are required for employees to feel psychologically safe:

Control and power

Managers have considerable control over various aspects of their employees’ professional lives, from salary and promotion prospects to performance evaluations and work assignments. This power encompasses not only tangible aspects like pay and job roles but also intangible elements such as an employee’s professional reputation, shaped by managerial feedback and assessments. The HSE (Health and Safety Executive) Stress Management standards give a clear view of just how much it is within a manager’s remit to be able to set the mood and tone of work environments for those in their teams.

To manage this power responsibly, it’s crucial for managers to foster an environment that maximises employee autonomy and choice within the constraints of organisational needs and goals. This involves offering employees options wherever feasible, such as flexibility in selecting projects, pursuing professional development opportunities and choosing work hours and locations when or if possible.

While the ultimate decision-making authority often rests with the manager, promoting a culture of open communication and providing choices can significantly enhance employee satisfaction and engagement. By actively involving employees in decisions that affect their work lives and offering them a sense of control, managers can build trust and foster a more positive and productive workplace environment.

Influence

Managers play a pivotal role within organisations as oftentimes unintentional role models due to their visibility and the precedence set by their achievements and behaviours. The way managers conduct themselves, the language they use and the strategies they employ are closely observed and frequently emulated by their teams. This heightened scrutiny means that even unintentional cues, such as a manager’s mood or offhand remarks, can be over-interpreted by employees, who might see these as reflections of their own performance or indicators of the organisation’s health.

Given this dynamic, it’s essential for managers to be consciously aware of their behaviour and the potential impact of their actions and communications. A manager’s mood or casual actions, such as appearing upset or distracted, can lead employees to mistakenly assume responsibility for these emotions, questioning their own performance or the stability of their work environment. Naturally the impact on managers themselves of this extra responsibility must be recognised, which is addressed below.

In today’s information-rich yet uncertain environment, managers are often seen as pointers for clarity and direction. Employees look to them not just for information but for interpretation and guidance on how various messages and organisational changes might affect them personally and professionally.

To mitigate potential misunderstandings and foster a more open and trusting atmosphere, managers can adopt a more transparent approach. By being open about their feelings, explaining the rationale behind their decisions, and communicating their values and how these influence their actions, managers can demystify their behaviours and reduce unnecessary speculation. Such transparency contributes to a constructive and authentic culture, reducing ambiguity and enhancing employee engagement and morale.

Identity, significance and ripple effect

Work is not just a place where people spend a significant portion of their time; it’s deeply intertwined with their sense of identity and self-esteem. Employees often find meaning and a sense of accomplishment through their roles, the skills they apply and the results they produce. Moreover, the workplace serves as a community where shared goals and collaborative efforts foster a sense of belonging and collective purpose.

The impact of work extends beyond the office or worksite. Research consistently shows that satisfaction and happiness at work can enhance overall life satisfaction, contributing to less stress and more happiness in personal life. The interpersonal relationships we have at work are the main driver of job satisfaction and 86 per cent of that is the relationship with management.⁵

Managers can play a crucial role in shaping workplace experiences by acknowledging and celebrating the unique contributions of each employee. Recognising the multifaceted roles employees play, both at work and in their personal lives, and fostering an environment of inclusion, openness and trust not only enhances workplace wellbeing but also contributes positively to employees’ lives outside of work. By doing so, managers not only improve the immediate work environment but also support the broader wellbeing of their team members.

But what about the managers?

Middle management is often recognised as one of the most challenging roles within organisations, more so than other occupational groups. They bear a significant burden of stress and workload, entailing the responsibility of driving results, implementing policies and motivating teams. Despite a general sense of job satisfaction, they are notably more prone to reporting their workload as overwhelming. With nearly one in four middle managers stating they often experience excessive pressure at work, the impact on their mental and physical health is a concerning reality. The stress levels reported by managers, especially those in certain salary brackets, underscore the intense pressures they face, with a substantial number expressing regret about their current roles and contemplating departure due to work-related stress.

This demographic, pivotal to the operational success of any organisation, faces a unique set of challenges that not only affect their personal wellbeing but also have broader implications for the health of the workplace environment, negatively affecting their ability to effectively support and lead their teams.

This highlights the critical need for organisations to provide robust support systems for managers, focusing not just on their professional development but also on their mental wellbeing. Stress management, building resilience and self-care are all key subject areas for Ripple&Co’s training programmes for managers. When delivering Talkworks and increasing managers’ EI to enable them to support their team members, the training critically extends to developing their competence in recognising and handling their own feelings, whether that is managing stress and overwhelm, impulse control or mastering anxiety.

Middle managers are not just cogs in the corporate machine; they are the linchpins that hold the organisation together, even more so now than ever given the nature of remote and hybrid work patterns that have emerged since the pandemic. Recognising their value and addressing their unique challenges is essential for building a resilient and successful organisation.

Ignoring the role of middle managers and their own wellbeing too can have significant financial implications for organisations. The costs associated with high turnover rates, decreased productivity and the potential for increased health insurance claims can be substantial. Investing in middle managers, therefore, is not just a moral imperative but also a financially prudent strategy.

Eileen Donnelly is chief executive and founder of Ripple&Co.

Employee wellbeing experts from Ripple&Co are speaking at the SHW Live (Safety, Health and Wellbeing Live) exhibition and conference in Manchester on 22–23 January. See:

For more information see:

linkedin.com/company/ripple-co

linkedin.com/in/eileen-donnelly

References

- DDI’s Centre for Analytics and Behavioural Research, 2019, tinyurl.com/m93fzfjc

- Mental Health at Work: Managers and Money, Workforce Institute, 2023, tinyurl.com/3u4b4nma

- National Safety Council, 2023, tinyurl.com/28rwcaf5

- Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle, 1984, tinyurl.com/5a8x8nmt

- De Neve, Oxford University, 2019, tinyurl.com/ym4shpv3

FEATURES

5 trends to watch in the safety sector in 2025

By David Head, Draeger Safety UK on 19 March 2025

Dräger’s annual Safety and Health at Work Report provides a useful insight and snapshot into the views of employees and managers on safety in UK workplaces. This year’s report suggests employers need to increase and refine their efforts in areas such as employee mental wellbeing, more structured safety training and greater use of digital and connected safety technology.

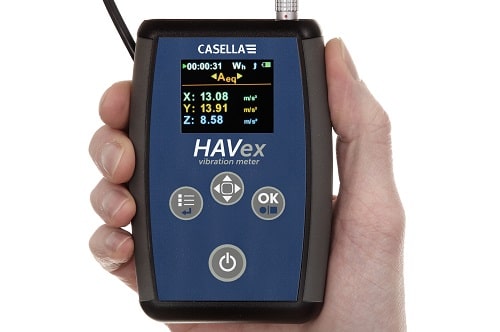

Get a hold on HAVS, before it’s too late

By Tim Turney, Casella on 18 March 2025

Employers may need to carry out measurements of hand-arm vibration from hand-held tools and machinery to identify if workers are at risk of debilitating and permanent damage to their fingers, hands and arms, but it’s essential the measurement equipment is used in the correct way.

The UK Hearing Conservation Association: how we work to promote the protection of the nation’s hearing health

By Leah Philpott, member, UKHCA At Work Group on 14 March 2025

The UK Hearing Conservation Association is a multi-disciplinary association that strives to prevent damage to the nation’s hearing health and other noise-related health conditions through a combination of practical, evidenced and cost-effective campaigns, awareness-raising activities and best-practice advice. It is therefore a great forum for those wishing to keep abreast of the latest developments around hearing health – both in the workplace and in recreational settings.